Before April, I was lucky to have gathered about 46 species on my annual list.

Since April, I have hit 100.

In less than 45 days, I managed to more than double my annual count… and I barely know what I’m looking at when I get out there. In the last two weeks, I’ve come home shaking my head in wonder at how the trees have absolutely filled with new and previously unnoticed song. On January weekends, I was able to park pretty much anywhere any time of the day at Colonel Samuel Smith Park on the Etobicoke lakeshore. Nowadays, I’d better get there before 7:30 am (6:30 am if it promises to be sunny), and I’d better be prepared to elbow my way through crowds of ornithological enthusiasts.

A Yellow-rumped Warbler not showing its rump.

I’ll tell you one thing… amateur birding is made a whole hell of a lot easier when all you have to do is watch the other birders and follow their lead. This past Saturday, one fellow brought his camera from his eye and hissed to his partner several yards away.

“Sweetie! Sweetie! Wanna get an Indigo Bunting?”

I may not be his sweetie, but my response was…

“Don’t mind if I do.”

I didn’t have my camera on that trip (walking the dog), but that beautiful blue bunting looked mighty nice through my binoculars, and now it’s #85 on my list.

The man-made Leslie Street Spit in Toronto — home to tonnes of old concrete, a natural reclamation, and thousands of birds.

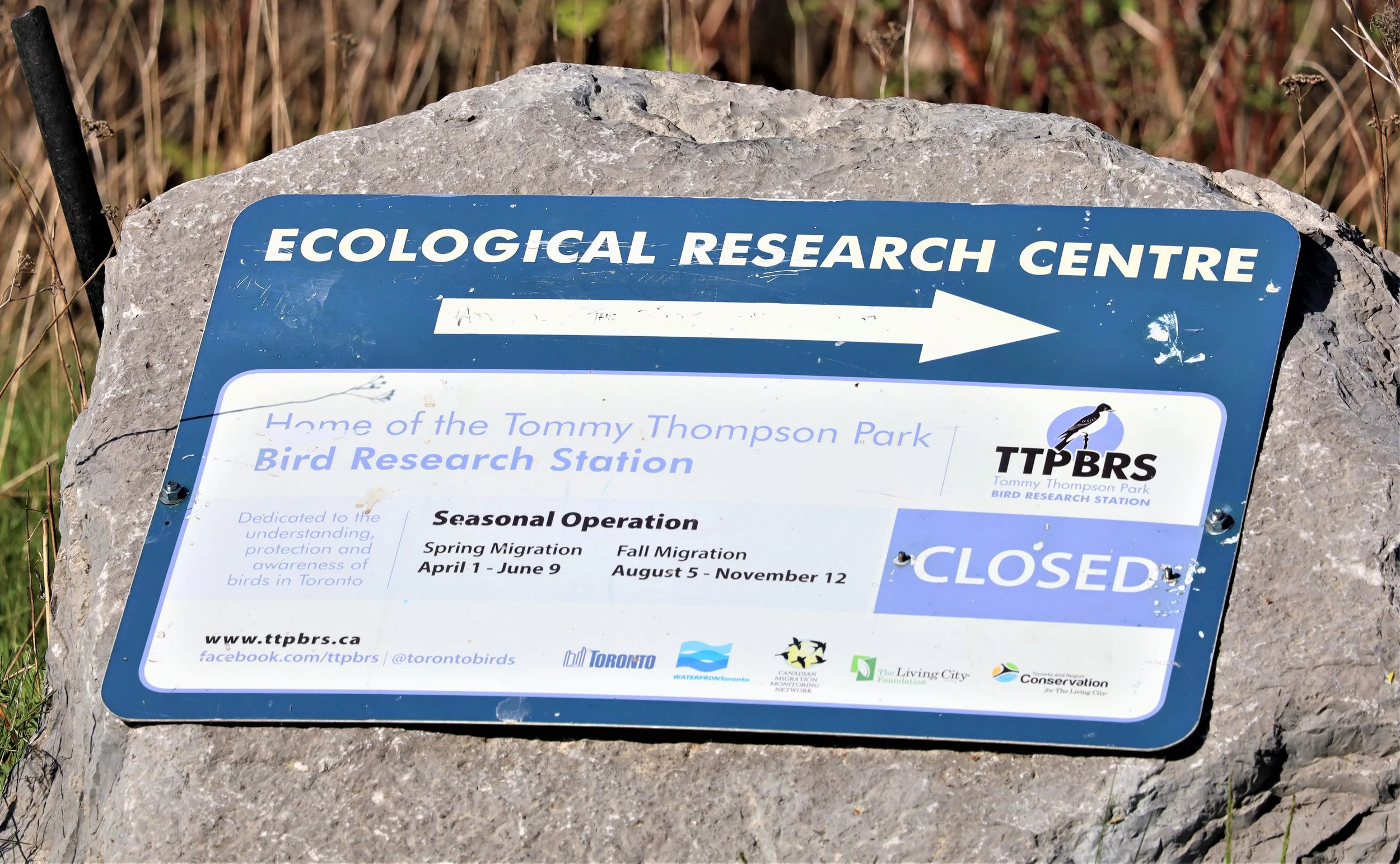

I filled out the rest of my century at Tommy Thompson Park on the Leslie Street Spit in Toronto’s east end. Not only is the manmade 5k peninsula (construction waste was intentionally dumped into Lake Ontario starting in 1959, to create a breakwater for Toronto harbour) a haven for migratory birds, but it is home to the Tommy Thompson Park Bird Research Station (TTPBRS), which tracks the over 300 species of birds that either live there or camp out for a bit on their way somewhere else.

Said closed; was open. NB: No pets allowed in Tommy Thompson Park, and no motorized vehicles (including e-bikes).

This time of year, the TTPBRS is in high gear, bagging, banding, recording, and releasing the many migratory fliers temporarily trapped in their carefully placed nets. I’ve visited the site two times so far this spring — brief stops of maybe ten minutes — and watched them record over 15 different species, wriggling and flapping away in their soft cloth bags.

A fresh catch of live birds, hanging in their soft cloth bags, waiting to be IDed, banded, and released.

I’m in awe of these volunteer conservational ornithologists, as they extract a bird, identify it by species, age, weight, and health status, place a tiny identification band around its leg, record all the data by hand in a paper log, and then release the slightly stunned little creature through PVC tubes set into the research station’s walls. My favorite part is when they gently blow aside the bird’s tummy feathers to ascertain the fat level beneath. A good solid layer of fat means the bird has likely been in the park for a while, feasting on its plenty. Little to no fat layer suggests a new arrival who used up their body’s fuel supply getting all the way from Central or South America to the north shore of Lake Ontario.

A Veery thrush gently and expertly handled by a Toronto and Region Conservation Authority worker.

Look, it’s the same Yellow Warbler from the top of this posting… well, unlikely, but a remarkable resemblance.

For the individual birds, they are in gentle captivity maybe half an hour, and then back out into the park’s trees, inlets, and pathways to mate, build nests, or just fatten up for a further long flight north. The TTPBRS website has all the info you need to better understand their work, to access volunteer opportunities, and to donate to the important work of migratory bird research. TTPBRS is one of many bird-banding and research stations in Ontario. Visit the website of the Ontario Bird Banding Association to learn more, including what to do if you find a banded bird (report it!).

Somebody loves the Pine Warbler, clearly.

“A forest bird never wants a cage. ”